Case Study: Johnson Street Trees

What a wonderful feeling it is to stroll leisurely down a leafy, tree-lined street! Would you like to collaborate with your neighbors to plant trees in the public right-of-way between your property lines and the street? Sausalito Beautiful would like to help. This case study identifies the key issues and success factors for the Johnson Street project, with the purpose of aiding efforts to add street trees in your neighborhood.

In 2017, the neighbors on Johnson Street replaced 18 trees in poor health with robust flowering plum trees. They chose the tree species based on the site and neighborhood character, then raised money to pay for their installation, and worked with the City of Sausalito to install the trees. Although these fruitless plums are still young, the neighbors are extremely pleased with all the benefits they bring to the neighborhood. You can learn from their experience when considering a tree-planting project for your street.

Johnson Street in April 2022

Why Street Trees?

The benefits of street trees are hard to overstate. Of course, street trees can convert a street lined with utility poles and street lights into a more aesthetically pleasing environment. Given the urban setting, street trees also provide pedestrians with protection from rain, sun, and excessive heat. Aesthetics and comfort aside, other benefits include:

- Economic: Mature street trees increase real estate values $15,000- $25,000 per home

- Safety: Street trees increase traffic and pedestrian safety because drivers slow down in a treed landscape, and the trees provide a buffer between pedestrians and vehicular traffic.

- Security: Trees improve general security in the neighborhood because pleasant leafy environments encourage people to walk and bring an increased pride of place.

- Ecosystem: Urban street trees provide the canopy, root structure and setting for an entire ecosystem of song birds, insects, and even bacterial life underground.

- Civic: Street trees can reduce the need for street drainage infrastructure while their shade can increase the lifespan of the surrounding asphalt.

- Environmental: They provide many environmental benefits such as reducing harm from tailpipe emissions, lowering ozone levels, intercepting pollutants, sequestering carbon, reducing noise, providing shade and buffering winds.

Street trees do require some effort on the part of homeowners, especially in the first couple of years. Sausalito ordinances require that street trees be maintained by the adjacent resident, just as with all the landscaping on the adjoining private property. More importantly, trees are an important part of our ecosystem, life which insects and birds depend on. This minor increase in personal responsibility, however, is greatly outweighed by the benefits that the trees bring. All things considered, street trees are a great investment and can significantly benefit your neighborhood.

Johnson Street’s trees were in bad shape

When Fay Mark moved to Johnson Street, she was deeply concerned about the scraggly English Hawthornes lining the sidewalk, including the one in front of her new home. The trees were planted in the late 1970s and had reached the end of their natural life. Most were dead, while others were in the process of dying due to irreversible issues such as trunk damage, trunk rot, and disease—which could be a safety issue given the strong winds in the neighborhood. The few that were living had large sharp thorns that could hurt children, dogs, or adults as they walked by.

Aesthetically, the trees were also a blight on the entire city. Johnson Street is quite prominent in Sausalito, with visitors and residents admiring the quaint harbor views while ambling down the sidewalk on the way to Caledonia Street for shopping and eating. In 2015, The Police and Fire Stations anchoring one end of the street had their landscaping upgraded by Sausalito Beautiful, which just made the rest of the street look worse.

Organization: a shared vision and a passionate leader

Over the years as she got to know her neighbors, Fay realized that many shared her vision of a greener, tree-lined street that they could be proud of. Along with John Farrell, she gathered the neighbors to talk about the possibilities and get an overall feel for the level of interest. A core group agreed to kickstart a project to replace the unhealthy street trees. Over time, Fay became the de facto leader given her passion for trees and training as a University of California Master Gardener (although she emphasizes that extensive tree knowledge is not a requirement to lead such a neighborhood effort).

One of the first things that Fay did was determine which of the neighbors were truly interested. She created a spreadsheet containing the details of each property in the two target blocks, the health of existing trees, whether tree cutouts existed in the sidewalk, how many trees were desired, and whether the owner preferred phone, email or in-person communications. Of the 22 residences on two blocks, 3 had an existing tree they wanted to preserve, 5 chose not to participate while 14 wanted one or two new trees. Thus spots for 18 new trees were identified.

A few neighbors wanted trees but either didn’t want to contribute money (some were just renters, others had a fixed income) or couldn’t maintain them (based on their age and health). In several of those cases, nearby homeowners offered to step in. Another situation arose where the owner wanted a tree but the underground utilities prevented planting one in front of their house. One person specifically did not want a tree—although technically they couldn’t prevent a planting in front of their house because the City owned the land, the group decided not to go against his wishes.

Throughout the project, the leaders were mindful to engage neighbors in the decision-making and keep them up to date on the progress. Several in-person meetings fostered a sense of community, with handouts detailing key decision points and expectations. At times, Fay went to individual houses, especially for those people who didn’t use email. Although not everyone was happy with every group decision, keeping people informed is vital.

A neighborhood project like this fosters a culture of shared responsibility, and one should never minimize the power of a group. For example, Fay found that when she went out to weed around her tree (and that of her 80 year old neighbor), people would emerge from their houses to weed around their trees. Inevitably, some neighbors are going to do more work than others.

Permitting: a collaboration with the City

Planting an individual street tree in Sausalito typically requires a permit because the City has a right-of-way for public transit over that land (regardless of whether the owner is a private citizen or the City). Fay understood the importance of collaborating with the Department of Public Works on a larger project like this, especially because she needed them to remove the old trees and create new cutouts, which can be an exacting task given underground utilities.

Fay worked with Loren Umbertis (Division Manager, Department of Public Works) whom she met previously to assess the health of the existing English Hawthornes. Knowing that the neighbors were on board, Fay and Loren sketched out a project plan, agreeing that the neighbors would pay for the trees and the City would pay for the labor. They decided to wait until fall to plant the new trees in order to give them a good head start with the winter rains.

Site Assessment: sunny but quite windy

The first core task in a tree planting effort is to assess the site, since the environmental conditions determine the possibilities, opportunities, and limitations. Johnson Street runs downhill towards Richardson Bay in the north-northeast direction; thus the trees would enjoy full morning and midday sun. With the coastal mountains at its back and its proximity to the foggy Golden Gate, the two-block residential neighborhood is quite windy with extensive summertime fog. While the sun exposure is ideal, the wind and fog create challenges for the trees. As a benefit, the canopy of additional trees would buffer the wind.

Much of Johnson Street already had tree cutouts in the sidewalk, but several people interested in new trees did not, so those would need to be created. Inside the existing cutouts, the soils were found to be quite rocky and nutrient-poor, so additional compost-rich soil would need to be added or substituted. The good news is that the slope of the street provided good drainage, since trees can suffer from root rot or crown rot in clay-rich soils that are on flat ground.

Tree Selection: several options based on suitability

The residents decided that they wanted all the street trees to be a single species in order to unify the look of the neighborhood. Plenty of other tree varieties could be found in the surrounding private gardens, providing diversity and preventing a monoculture that could be susceptible to diseases. In order to aid decision-making, Fay kept track of all the factors to be considered when deciding on the specific species.

Given the site assessment, the list of requirements for the optimal tree species were:

- A non-invasive root structure that wouldn’t tear up the sidewalk

- Tolerates the summer winds, salty marine air, and poor soils

- Drought tolerant so that it wouldn’t require extra watering once mature (irrigation would not be connected to the trees)

- Relatively short mature height so that the trees didn’t interfere with utility wires or obstruct views from the homes.

- The first set of branches needed to be at least 7 feet above the sidewalk

- Expected to flourish in the sun, in Sausalito’s climate (Sunset Zone 17, USDA Zone 10a).

Beyond what the site required, the neighbors had several ideas for what would be nice to have in their street trees:

- Flowering (for beauty) yet non-fruiting (no extra litter)

- Evergreen to provide beauty all year, thus no seasonal litter

- Ecosystem-friendly to encourage native insects and birds

- Attractive bark, for additional interest as people walk by

- Quick growing, reaching mature height soon

- Reasonable cost and availability

To find the larger list of potential trees, the leaders first consulted several local professionals including landscape architects, landscape designers, and a certified arborist. They also took a critical look at the trees that performed well in surrounding areas with the same microclimate. Then they looked at local technical sources such as California Native Plant Society, Marin Master Gardeners, Urban Forest Ecosystem Institute, and Fire Safe Marin. They also considered the approved Street Tree List for Sausalito, understanding that this list had not been recently updated. A long list of thirty tree species was eventually narrowed down to three options based on the requirements and site suitability.

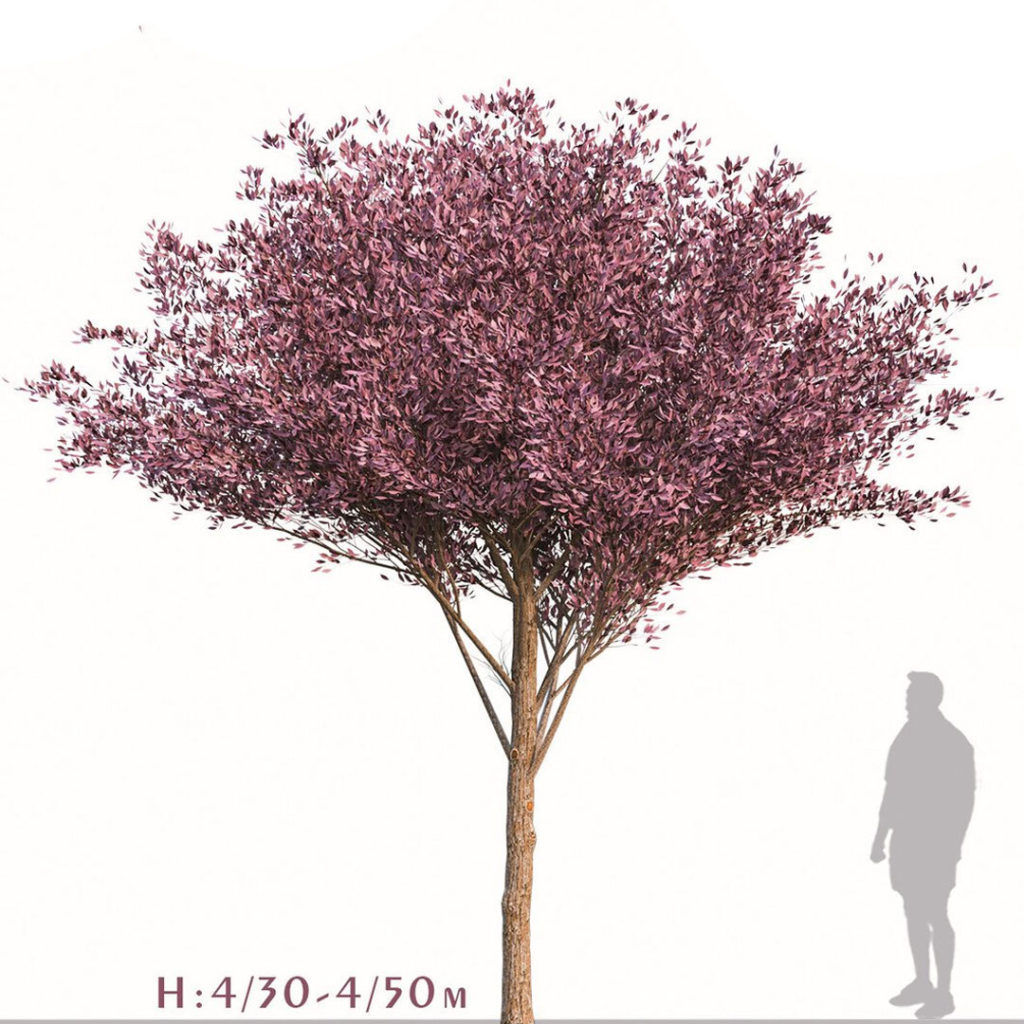

At an in-person meeting, the neighbor group was presented with information on each option and made the final choice: Prunus cerasifera ‘Purple Pony Plum’, a fruitless tree that is utility- and view-friendly with a maximum height of 15-20 feet, tolerates Sausalito’s summer winds and salty marine air and soil, has a non-invasive root structure, is drought tolerant once it matures, and produces beautiful pink blossoms in the spring. Although plum trees are deciduous, they lose all their leaves once a year which would contain the “litter.” Based on cost and logistics, they decided to purchase mid-sized 15-gallon trees, since a larger 24” box tree would have had difficulty fitting in the sidewalk cutouts.

Prunus cerasifera ‘Purple Pony Plum’

Financing: Neighbors paid for trees, City paid for labor

Budgeting and financing are key factors to consider for any project. When many individuals are expected to participate financially, It’s also important to think about where donated monies will be held, and how to pay vendors. The Johnson Street team decided to put together a two-year budget, then raised money from neighbors based on the number of trees installed on their property. Sausalito Beautiful can assist in projects like this by providing a website for processing credit card donations, depositing the money and any checks in our bank, keeping track of your project funds, and subsequently paying vendors.

The major tasks and budget items for Johnson Street trees for the first two years were:

- Site preparation: removing existing trees, adding sidewalk cut-outs, amending soil

- New Tree cost: including tax and delivery

- Planting cost: including materials such as fertilizer, mulch, stakes, straps

- Pruning for first two years

- Additional costs: fertilizer for two years, mulch for the second year

Fay negotiated with Sausalito’s Department of Public Works (DPW) to perform some of the labor themselves and cover the labor costs of a contractor to do the rest. Thus DPW agreed to remove ten existing trees and add two sidewalk cutouts themselves, while paying the contractor approximately $3,200 (in 2017 dollars) for tree delivery and placement, tree installation, soil amendments, and planting materials.

The residents contributed $250 for each 15-gallon plum tree including pruning for two years. A local landscape designer hand-selected the best trees from Urban Tree Farm in Santa Rosa. The rest of annual maintenance costs (mulch, fertilizer, and water) were estimated to be $15 per year. The expectation was set that, in the future, a major pruning would cost around $40 per tree (assuming all the trees were pruned by one person).

Planting: the fun part

The neighbors came out on a balmy October weekday to watch the inspiring sight of eighteen plum trees being installed on either side of two blocks on Johnson Street. Contractor Tony Graceffa of GSI Landscaping led the planting, with Kellee Adams assisting. Part of the street had been blocked off so the GSI crew could incorporate new soil and plant the trees without any issues. For each tree, they removed the nursery stake and used a leveling device to make sure the trees were upright. Then they pounded in two new 2” thick stakes, using straps to secure the tree yet allow a bit of movement to encourage strong root development. Finally, they watered the trees using hoses which the neighbors were asked to leave out. As the last tree was watered, there were smiles all around.

The entire installation took place over two weeks including preparation and followup, with new concrete poured in sections of the sidewalk that had been damaged due to root invasion and age. The preparations involved the DPW crew removing the existing trees using a backhoe. They then created the new sidewalk cutouts and broke up old soil inside all the cutouts. Fay also coordinated the delivery of the trees and several yards of soil from A&S Landscaping in San Rafael.

Fay Mark (Project Leader), Kellee Adams (Dig-It Landscape), Loren Umbertis (DPW), and Tony Graceffa (GSI Landscaping)

Maintenance: on-going tree care should be planned

In the first two years after planting, the new trees require some maintenance, tasks which are critical for long-term viability of the trees. Fay made sure that the participating neighbors were well aware in advance of the maintenance tasks they were expected to perform or finance.

The main tasks are:

- Watering: especially during the summer

- Pruning: critical around year five

- Mulching: improves soil health and thus long-term tree health

- Fertilizing: improves tree health

Assuming trees are planted in the fall with the oncoming rain, the young trees must be deep watered on a weekly or bi-weekly basis throughout their first two summers, Of course the spring rain conditions will dictate the exact irrigation schedule. Because there were no irrigation lines nearby on Johnson Street, watering needed to be done by hand on a house-by-house basis, using garden hoses stretching 15’ out to the sidewalk. In this case, the task was performed by the homeowner or their gardeners.

Pruning is another maintenance task which is important, although only critical around year five. Because space was tight and everyone wanted to encourage tree growth parallel to the street (as opposed to over the sidewalk or street), a light pruning was done on the Johnson Street trees at the beginning of the first and second summers. (Be sure to check with an arborist for the right time of year to prune your chosen species). A single professional pruner trimmed all the trees one day, paid for by the initial fund raising. Pruning in the first few years is optional, but after about 4-6 years in the ground, the trees will need a more extensive pruning in order to ensure a good long-term structure. Note that pruning tasks are best left to professionals, preferably those certified by the Aesthetic Pruners Association.

The trees should be mulched as needed (e.g., every two years), an event which could turn into a fun neighborhood-wide gathering (maybe even with a potluck meal afterwards). If additional people are desired, Sausalito Beautiful’s Green Thumbs volunteers could be invited. While not critical, mulch conserves soil moisture by increasing water infiltration and slowing evaporation. As it decomposes, an organic mulch improves soil structure, fertility, and aeration, thus vastly improving the long-term health of the tree. On Johnson Street, a coarse bark mulch was added every spring because the winter rains often washed it away given the grade of the hill.

A fertilizing regimen depends greatly on the tree species and soil conditions. Typically, an initial fertilizer is added upon planting. Then compost can be layered on as a mulch just before the rains start so that its nutrients can soak into the soil. Between compost and a coarse bark mulch, no additional fertilizing would typically be needed, but check with your landscape professional.

Transitions: change is inevitable

Don’t forget to consider the potential future changes in neighborhood leadership and home ownership. A multi-block street tree effort needs to have a clear leader to start, and it’s also important to plan for future leadership change. The initial leader may move away, may take on a new job that requires more time, or just may not feel up to the task at some point. Thus it’s important to involve others who could become future leaders, and document the project as much as possible (e.g., money raised, long-term maintenance schedule, arborists and pruners used, material purchased).

In the case of the Johnson Street trees, the initial leader Fay Mark moved away in 2021. She passed the baton to Martha Nelson, who was one of the neighbors sponsoring a tree. Martha has just the get-it-done mentality needed to take over and the transition has been smooth, with Fay continuing to be available to answer questions.

Another challenge arises when a home is sold and the new neighbors do not feel the same sense of ownership over the trees. When a new owner moves in, especially if it is in the first few years, the project leader should bring them up to speed on the tree project and encourage them to participate. If they don’t have the desire to take over the maintenance of the tree, perhaps an adjoining neighbor would volunteer to look after it.

Be prepared that not all the trees will survive. An urban setting with poor soils can be challenging for tree health. Five-year survival rates are higher for tree species with low water use demand, as well as for properties with stable homeownership. Although all the Johnson Street trees were healthy, someone vandalized several of the trees in 2021. Two of them had to be replaced, using monies left over from the initial fundraising.

Critical success factors for street tree projects

The following enabled the Johnson Street project to be successful:

- One or two leaders who have a real passion for the project and the organizational skills to get it done.

- Several in-person group meetings to share thoughts and ideas, while building a sense of community

- Early buy-in from Sausalito’s Department of Public Works

- A means of tracking interested neighbors, contact information, and site details

- A clear plan detailing responsibilities, yet allowing flexibility to adapt to changes

- A list of requirements and “nice-to-haves” to help with tree species selection

- Setting realistic expectations with neighbors as to the tasks, responsibilities, and costs so that no one is surprised.

- A buffer in the budget to handle unexpected expenses, using leftover monies for future tree replacement or maintenance.

Sausalito Beautiful can help

Sausalito Beautiful helps mobilize the community to improve our public green spaces. While we did not play a prominent role in this project because the neighbors were self-sufficient, we are ready and willing to help you in your quest to plant trees along your street. Depending on your desires, we can help with:

- Understanding the entire process

- Connecting you with landscape architects and arborists and other resources

- Providing seed money or challenge grants

- Serving as a fiduciary to collect and disperse funds that are raised

- Working with the City of Sausalito and the Department of Public Works

- Organizing work days with neighbors and our Green Thumbs team